My relationship with Raleigh began on Mother’s Day in 1961 when I was eight years old and continued for eleven blessed years.

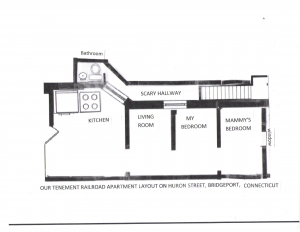

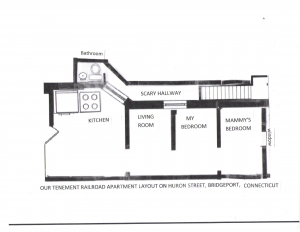

I was living on Huron Street where I lived in a railroad tenement with my grandmother and mother, who both worked full-time jobs. Our top-floor apartment was run down but immaculate and was laid out in a single long line of rooms: from the kitchen to the living room, to the bedroom that I shared with my mother, to my grandmother’s bedroom at the end.

The tiny bathroom was directly off the kitchen to the left and lined up with a long narrow hallway that ran from the bathroom all along the length of the entire apartment and ended up at a dark, steep and narrow stairwell that led down twenty steps or so to the front door. We never used that door, because it was padlocked—sealed shut and unusable. So the only way in and out of the apartment was to climb the several rows of steep stairs in the back of the house and enter through the kitchen. Only one way in, and one way out. A real fire trap.

My grandmother Mammy (pronounced MayMe) worked the 3-11 pm shift, so she was already gone by the time I got home from school. My mother worked until 6 pm or so. I didn’t like coming home to an empty apartment at all. What eight-year-old would?

Every day after school I would slowly trudge home. Then I would anxiously climb the stairs upon stairs in the back of the building and hole myself up in the kitchen until my mother came home.

And in the winter when the sun would set super early, I was a bundle of nerves—tense and agitated. Because scary things inevitably came out when it got dark in that crummy apartment on Huron Street.

I would continuously and frantically check the clock in the kitchen as it got closer to the 6:15 mark while sprinting from one end of the apartment to the other, to press my face and hands against my grandmother’s bedroom window in the hopes of catching a glimpse of my mother arriving home.

I would furtively check out the street below for a mother sighting and then race as fast as I could back to the kitchen, my mind full of monstrous thoughts about the dark hallway. During that time in my life, I had a recurring nightmare that troll-type demons were lurking at the bottom of the stairs, waiting for me. That damn dream didn’t help the situation at all.

I would rock myself on a kitchen chair, willing my bladder to cooperate so I wouldn’t need to go to the bathroom and face the dreaded scary hallway.

I finally got up the courage to tell my grandmother that I was afraid to come into our empty apartment. I tried to play it down because I didn’t want her to worry about me. Plus what I told her was sort of true: I was more lonely than afraid.

“The poor dear is lonely,” she repeated to my mother soon after that, as I listened intently while pretending to color at the kitchen table. As they discussed the situation, they glanced over at me, and when I curiously looked up at them, in hopes of hearing their solution to my predicament, they finished off their conversation in French.

A few weeks later, my mother treated Mammy and me to an elegant and very expensive Mother’s Day brunch at the Lighthouse Inn in New London, Connecticut.

Now, this brunch was way beyond my mother’s means, but it was Mother’s Day after all, and it was also a rare day that we ever went out to eat.

I recall the Lighthouse Inn being the grandest place I had ever seen, and incredibly fancy, with magnificent views of the Thames River, as well as the Long Island and Fishers Island sounds.

At the time I didn’t know what the bodies of water were called, but they most definitely left a lasting impression on me. So much so that 56 years later I can still recall that Mother’s Day like it was yesterday while most other memories from later in life are a bundle of murk and haze.

There was an elegant pathway leading up to the Lighthouse Inn, which was set way back from the main road. Both sides of the path up to the mansion-turned-Inn were spilling with the brightest and most beautiful wildflowers, roses, asters, and goldenrod.

Before we reached the front door of the Inn, there was a magnificent fountain sitting inside a circle of lush meticulously manicured green grass.

The entire scenario reminded me of the royal estates I had seen many a time on the “Million Dollar Movie.” For anyone that remembers the series, they would show the same movie twice every night from Monday to Friday, and then three times a day on Saturday and Sunday. The “Million Dollar Movie” music was “Tara’s Theme” from “Gone With The Wind.” So as I strolled up to the grandiose entrance of The Lighthouse Inn, I hummed the iconic tune quietly to myself.

While I stuffed my face with eggs benedict, and hordes of crispy bacon, I was pretending that I was one of the rich and the famous. I play acted in my mind and ordered a Shirley Temple.

After brunch, the three of us decided to throw pennies into the fountain and make a wish. The fountain area was packed with families who all had the same idea, and as we squeezed in and out of the crowds toward the fountain, Mammy suddenly and violently began to throw up.

Well, that dispersed the crowd rather quickly. And to their horror, Mammy’s top false teeth flew out of her mouth and onto the green leafy grass. My mother and I looked at my grandmother in shock as she bent over and picked up her teeth, shook off the vomit, and popped them back into her mouth. When she turned toward us, she casually and matter of factly said, “The food was too rich.”

My mother was humiliated and wanted to get the hell out of there. I was in no rush—and intent on throwing a penny into the fountain. She dragged me to the car, all the while talking under her breath about how embarrassed she was and how she couldn’t take us anywhere without us causing some kind of an incident. Poor Mammy was nauseous as all get out.

We got into our rickety old car, and it took a few tries before the engine turned over. My mother was frustrated, and I figured our Mother’s Day outing was over—ruined by Mammy’s teeth flying out of her mouth.

We drove for a while and came to a white house with a large red barn-like building. Mammy, who was still feeling queasy, stayed in the car. My mother took my hand and together we walked up to the house, and she rang the doorbell. An elderly woman answered the door and chattily walked us to the barn.

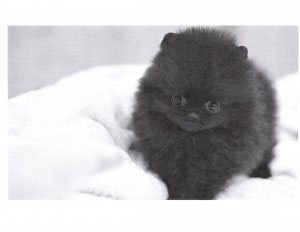

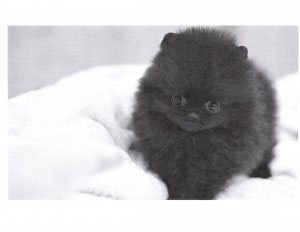

The woman opened the latch to the barn and lo and behold, there was a pile of black fluffy puppies! I was having a hard time trying to figure out why we were there with these adorable fluffballs and ran back to the car to get Mammy.

When I got back to the barn with Mammy, the woman handed me the tiniest and most precious black powderpuff puppy I had ever seen. “He’s a pedigree Pomeranian,” my mother told me proudly as he fervently licked my face with his teensy red tongue. I was still confused as to why I was there.

“He’s yours,” Mammy said lovingly. “Someone to keep you company,” my mother added. The woman pulled out a folded paper from an envelope as I crushed the little black snowball against my chest.

“His mother’s name is Marlene, and his name is Marlene’s Onyx Jet,” she explained as she presented my mother with his “papers.” “His name is Jet,” my mother reiterated to me.

Jet? I didn’t like that name. It didn’t suit my puppy at all.

“What’s his father’s name?” I inquired. “His father? Who cares?” Mammy responded. The woman pointed out a name on the piece of paper and replied, “His father’s name is Sir Walter Raleigh.”

Sir Walter Raleigh! Now that was a fitting name for a dog with papers!

“I’m calling him Raleigh,” I informed them both, even though they thought it was an overly pretentious name. On the way back to Huron Street, they tried to convince me to call him something else, but my mind was made up. His name was going to be Raleigh, and that was that.

It was a Mother’s Day I will never forget. Poor Mammy asked my mother to pull off the side of the road so she could throw up again, and right before we got to Huron Street Raleigh puked all over my new dress.

I often look back at that time in my life and refer to it as before Raleigh and after Raleigh. Before that Mother’s Day and after that Mother’s Day.

Now with Raleigh in the picture, when the school bell rang, I would ecstatically race back to our apartment, fly up the stairs upon stairs, and burst into the kitchen where my too- fancy-for-Huron Street pedigree puppy would be patiently waiting for me.

The bathroom? No problem. The hallway? Easy breezy. Raleigh would growl and bark at anything he thought was moving about. Heck, Raleigh would bark at the air. He thought he was a Great Dane, and I guess whatever was lurking around thought he was too because nothing scary ever showed itself when Raleigh was around.

I had no need to sprint from one end of the railroad apartment to the other, furtively looking for my mother. And I wasn’t afraid of the dark any longer.

I was too busy dressing Raleigh up in pink tutu’s and teaching him to dance on his hind legs. Or I would whip him around the kitchen with his tiny teeny little front legs.

I look back on it now, and I hope I didn’t hurt him, but he loved every minute of it, the two of us swirling and spinning full tilt in circles until I would fall down. Then the two of us would dizzily try to walk it off. I would laugh uncontrollably. He would bark playfully.

From that Mother’s Day forward it was always Raleigh and me—my best friend, my fierce protector, my favorite sidekick, my beloved brother.